As a follow up to Patent No. 2457 lodged by Daniels, this piece is certainly of significance. The Daniels instruments sought to display greater resolution with the introduction of a geared sub-assembly greatly magnifying the small rotational movement of the primary arbor, that connected by a fine chain to the secondary lever – the result being that the main dial had a very open scale, the subsidiary a much coarser one.

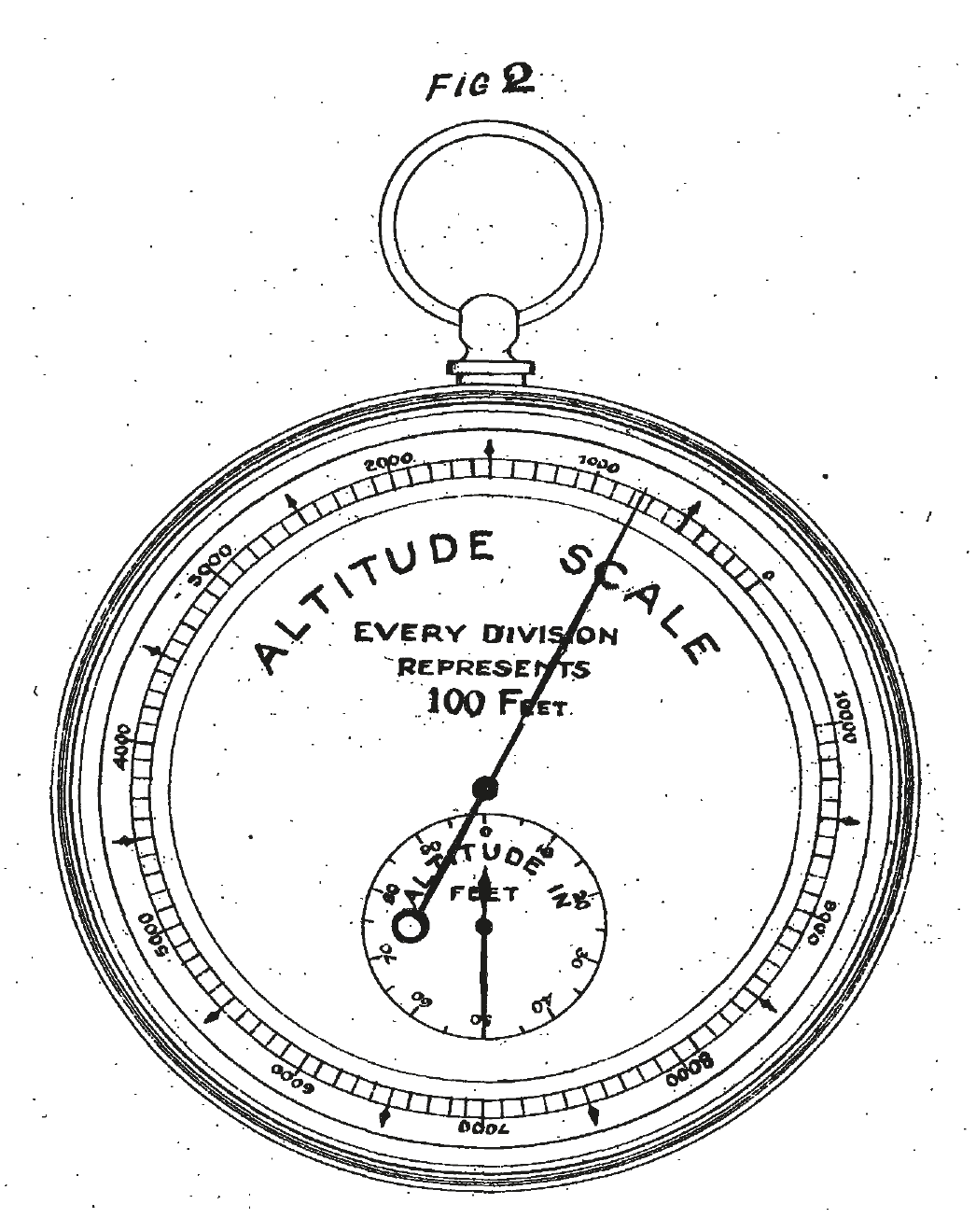

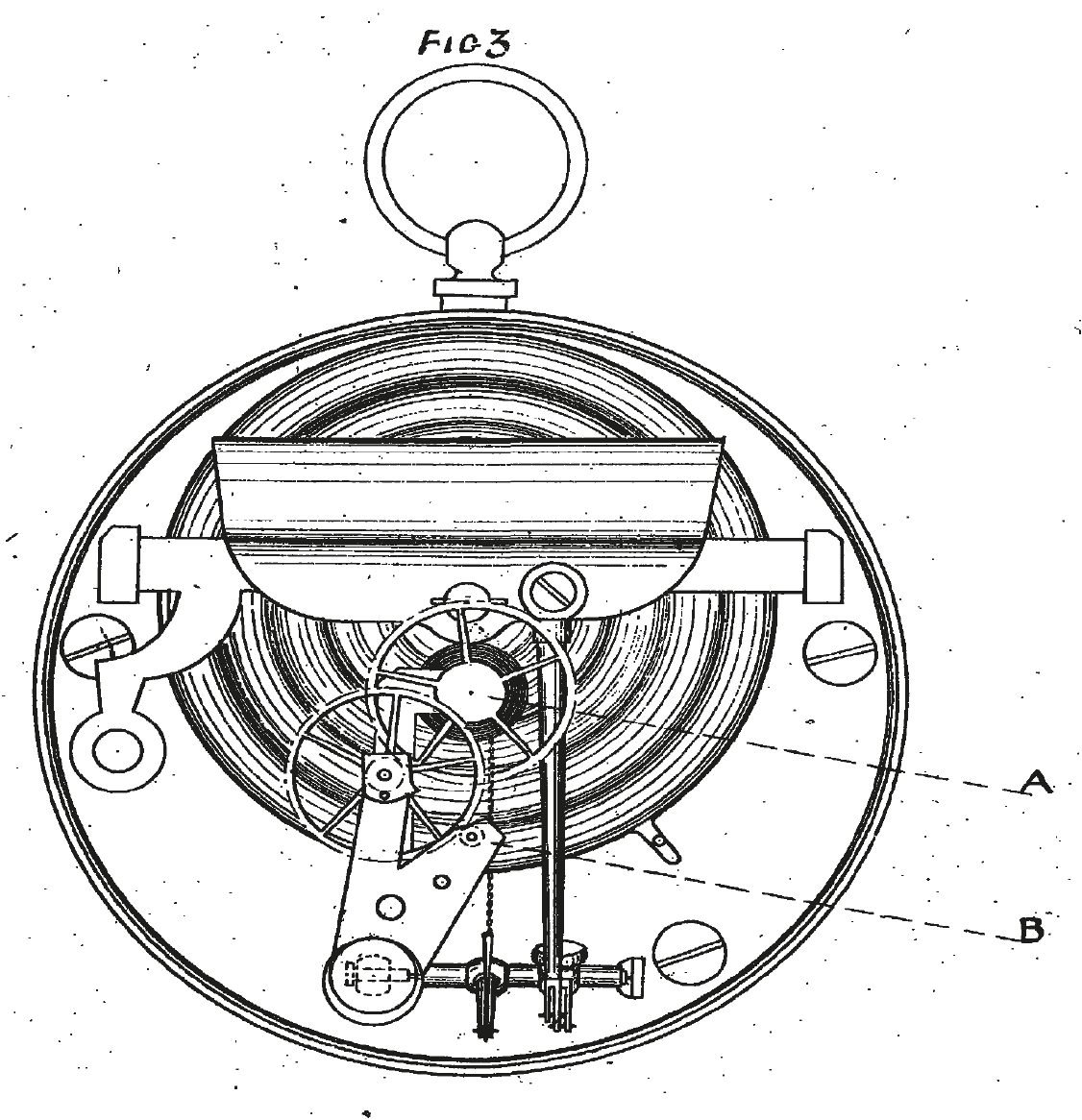

In essence, the Astens Patent No. 2853 of 1907 is the reverse of the Daniels patent, achieved by near identical means. Here, a highly developed movement, based on a conventional Vidi pattern driven from a single 1” nickel silver capsule, has the central main dial arbor fitted with a fine toothed spoked gear driving a fine pinion positioned below the subsidiary dial set in jewelled bearings.

To say that this is a rare piece is certainly not to overstate. I believe I might have seen one other some years ago, but that said it might well have been a copy manufactured after the expiration of this patent No. 2853.

It is clear from examination of the patent that the train in this piece is markedly different from the drawing, in which two fine gears of similar diameter provide the necessary amplification. This patent design is substantially less efficient than the instrument here shown, and it may be that No 30 is in fact a development from the original. Manufacture of the large, centrally mounted wheel would have been a more involved enterprise where accuracy for run out and flatness is critical.

As is so often the case in engineering, where gains may be found in one aspect, associated losses are found in another. Developments of the aneroid system are a fine example of this.

So how important is this? In practical terms, it was clearly not a success otherwise this very obscure patent would be more widely seen. The lack of success was almost certainly a function of mechanical issues, principally friction and the certainly that transition across the pressure gradient would have been hesitant. In addition, this would have cost at least double that of a standard instrument to produce. Then, of course, vulnerability to damage with such a finely executed train would always have been an issue.

All that said, commercial success is not always a benchmark for significant design, which this is. Perhaps not as significant as the original Daniels Patent, this is nonetheless a fascinating commentary on the perpetual quest for greater resolution and accuracy.