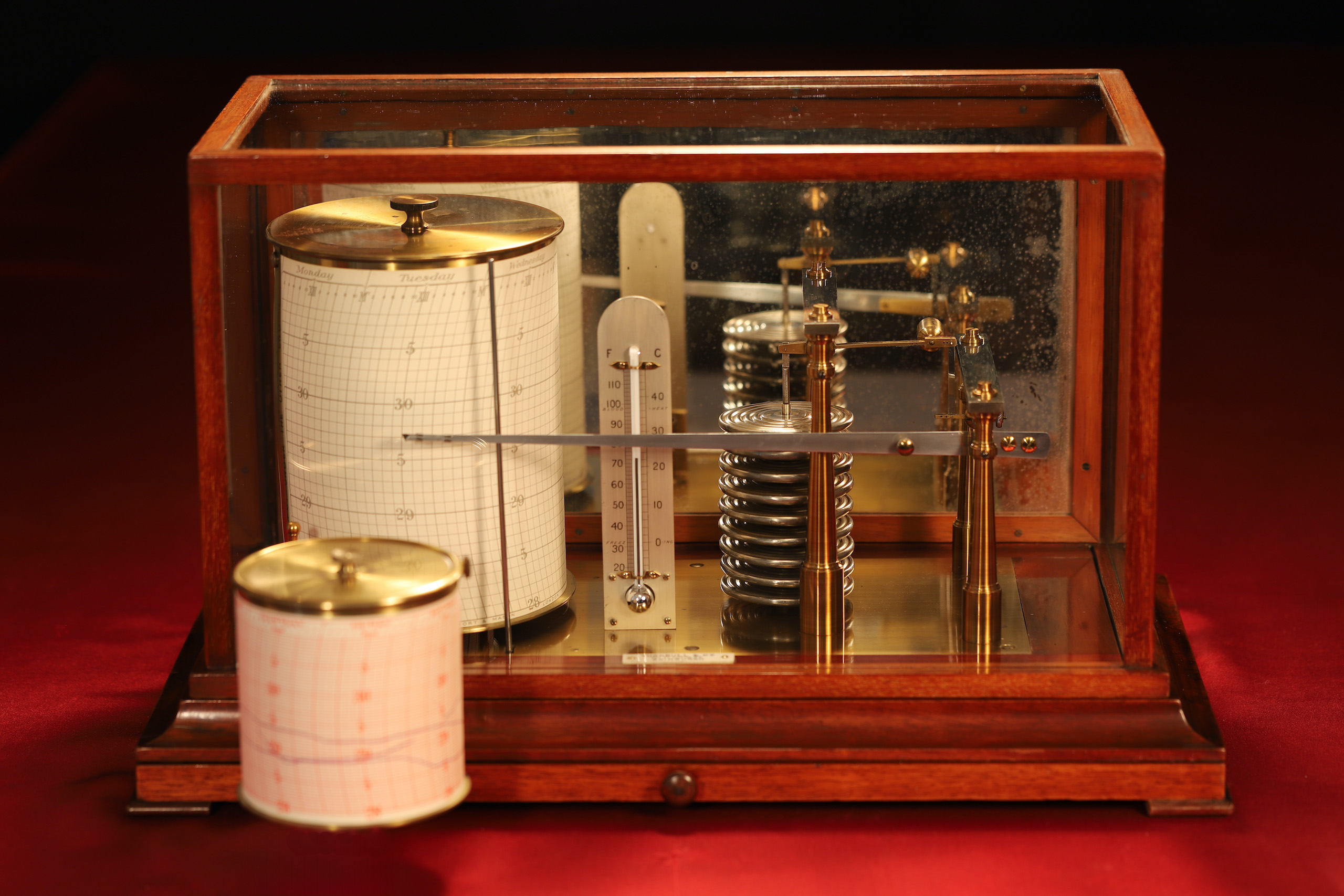

Another fine instrument of particular interest, this large barograph is something quite special, and although unsigned, is undoubtedly the work of Negretti & Zambra. Let’s examine the evidence for this.

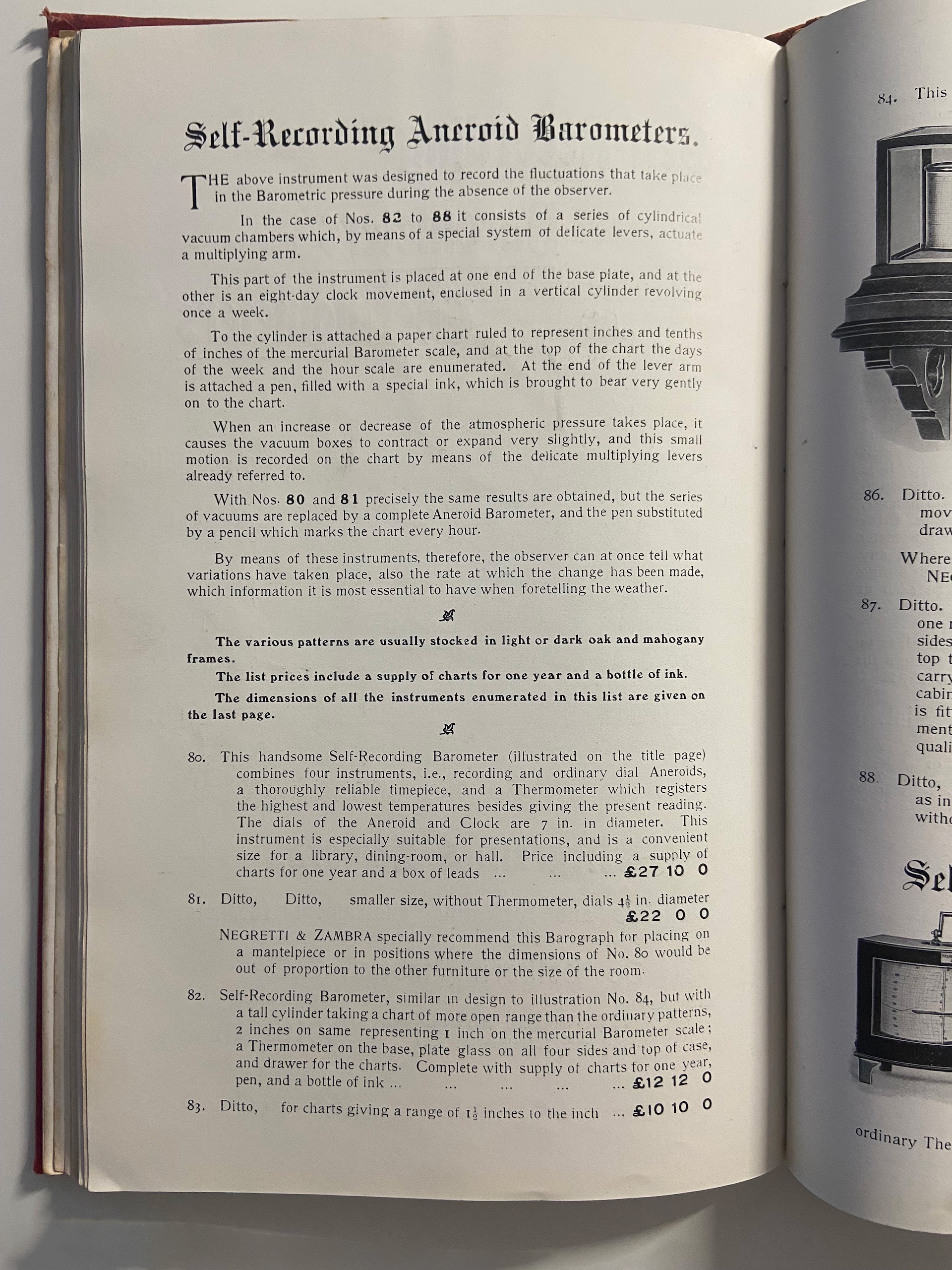

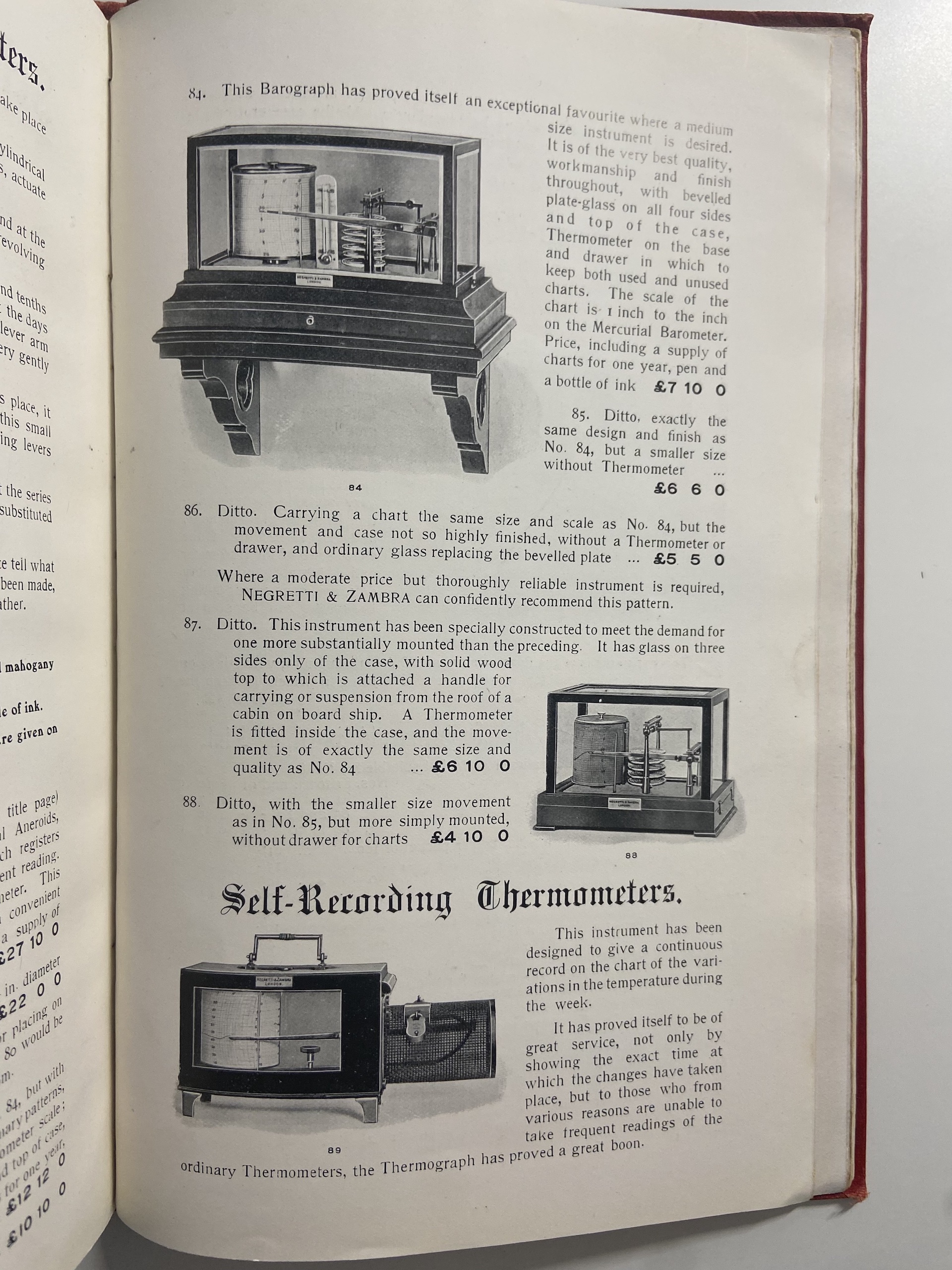

First, the instrument is listed in the Negretti & Zambra catalogue of 1910 in the section Self-Recording Aneroid Barometers: item 82, a “Self-Recording Barometer, with a tall cylinder taking a chart of more open range than the ordinary patterns,” and although there is no image of this barograph, the entry refers to the illustration of a regular instrument that is strikingly similar in style, though this barograph’s drum with a height of 7″ dwarfs a standard drum at 3¾”. Priced at £ 12 12 0, almost double that of the regular barograph, sales of this larger instrument will have been modest, and very few of these barographs are seen today – I have seen four examples over the years.

Up until, and probably after, this instrument was produced, Negretti & Zambra had been the major importers of barographs by Richard Frères of France, undoubtably the finest instruments of their time and still performing outstandingly well today. At some point, though, Casella entered a partnership with the French firm and one of the pieces, a very unusual early weather station, in the Vavasseur Archive is almost certainly amongst the first of that collaboration. Negretti & Zambra saw the need to produce their own instruments, not only because of the economic advantage in so doing but perhaps forced into the decision with the close alliance formed between Casella and Richard Frères.

So what other evidence is there that this is Negretti & Zambra built? Well, the cabinet conforms very closely to the then style of their cabinets, including the hinged glazed cover. Many design cues are taken from the Richard Frères instruments, notably the arrangement for adjusting to zero, and in both Negretti & Zambra and Richard Frères instruments the pressure sensing cells are mounted on a heavy spring brass platform. Richard Frères generally adjusted this from beneath with a key – Negretti & Zambra chose to provide for top adjustment with a very elegant spindle terminated at the top with a convex engine turned knob and at the bottom threaded into the chassis, the projection of which bears on the spring brass platform below. When turned in either direction the platform is raised or lowered, in turn causing the pressure sensing capsules to be raised or lowered.

The cross beams are steel, grained and lacquered in precisely the Richard Frères manner: superficially this might seem unnecessary, but there is a reason for the selection of steel over brass and it relates to the very precise nature in which Richard Frères barographs were constructed. The turned columns on which the cross beams are mounted maintain the pivots for the spindles or cross shafts. The setting up of end float of these spindles is very important for the overall performance of the instrument. Since this setting is very fine, any expansion or contraction through temperature fluctuation of the cross beams will affect the setting of the pivots. For all the obvious advantages of brass in the construction of scientific instruments, the material suffers from a particularly high coefficient of expansion, steel a very much smaller one. The effect of this will be to draw together or force apart the columns and thus perceptibly change the pivots’ setting and thus the end float of the cross shaft. The use of steel in this context is another piece of good evidence as to the lineage of this instrument.

Temperature compensation has always been an issue with aneroid systems. Indeed it became a real bone of contention mid-way through the last quarter of the C19th, makers becoming more and more anxious to assure prospective clients that their instruments had been rid of this undeniable curse. Whilst I was re-building a barothermograph, definitively Negretti & Zambra, I noticed an innovation, unknown on any other contemporary instrument. The primary lever, that which connects to the top of the pressure sensing cells and swings about the first spindle, was in fact a very elegantly engineered temperature compensator, the component itself of generally much lesser thickness than accepted practice, and appended to its lower surface a steel strip making a form of bi-metallic compensation. The barograph currently undergoing restoration has this same innovation and the execution is near identical.

The pressure sensing capsules, in this case nine autonomous cells, are of a pattern and material absolutely consistent with other Negretti & Zambra instruments of this era: they are all a high silver/nickel alloy, and the design is common across the range.

Looking slightly deeper into the execution of this instrument when stripping it down, it was immediately obvious that the bolts that passed from beneath the chassis into the bases of the columns had unformed heads, ie not hexagonal or slotted, but simply round in section. I have observed this anomaly on one other instrument, a “Jordan” barograph which we know for certain is the work of Negretti & Zambra, and contemporary to this instrument. I know this is a small detail but nonetheless it is a telling piece of evidence when comparing these unfinished bolt heads which exhibit precisely the same finishing marks and appearance in both instruments. These unformed heads may seem like an oversight, one might even say of poor making, and that might be so. It is not something that one would find in an instrument by JH Steward or Callaghan but then Negretti & Zambra at that time were not really in the same league.

Another interesting piece of evidence surrounds the inclusion of a serial number, “2049,” struck into the edge of the chassis in a rather distinctive manner, and similar to that found on the “Jordan” barograph and the barothermograph mentioned above. This might well suggest a serial number range that included an array of related types of instruments.

There are many other indicators that suggest Negretti & Zambra as the maker, though it could be argued these are in the main subjective. This instrument is white-labelled to “Turnbull & Co, 60 Princes Street, Edinburgh,” another maintained in the Vavasseur Archive is white-labelled to “J. Brown, 78 St Vincent Street, Glasgow,” a third was actually labelled “Negretti & Zambra” and sold at public auction for a small fortune in 2022. Some years ago I observed a fourth, though I have no information at all about it.

By any measure this antique barograph is a very impressive instrument. Generally the making is of a high standard, and the concept of a much more open scale, magnifying one inch of mercury into two inches of vertical travel, makes for a trace with noticeably better resolution. The scale of the components is about twice that of a conventional barograph, rendering this barograph an instrument not only of quality and performance but of very strong aesthetic appeal.

All the normal operations involved in the conservation of these instruments are being performed here, from the disassembly of the case, removal of the glass to enable proper cleaning, careful conservation of the timber frame and plinth. Then to the movement which has been completely stripped, each component carefully cleaned and inspected, the lacquered surfaces cleaned and conserved, preserving the original finish, its texture and colour.

Replacing parts that are no longer serviceable is always an issue as the prime objective is to keep the instrument as original as possible. If a part is bent it might be straightened; a missing part may often be sourced from our large stock of original spare parts. In the case of recording arms, often the fine nib end has corroded away leaving the arm too short. This has the negative affect of changing the amplification of the original signal. Additionally, because the arc of the arm has now changed it will not follow the described arcs on the recording chart.

I make arms here from scratch precisely to suit each instrument. They are cut from thin aluminium sheet, the mounting holes formed and the surfaces then prepared in keeping with the original, sometimes grained and lacquered, sometimes raised to a high polish. This is a time consuming process but actually the only route to a satisfactory outcome.

The re-assembly is the part that really takes the time though: careful alignment, resurfacing of pivots, re-balancing and calibration are all vital steps in producing the very best from an instrument that is around 115 years old.

When finally completed, this instrument will be offered for sale.